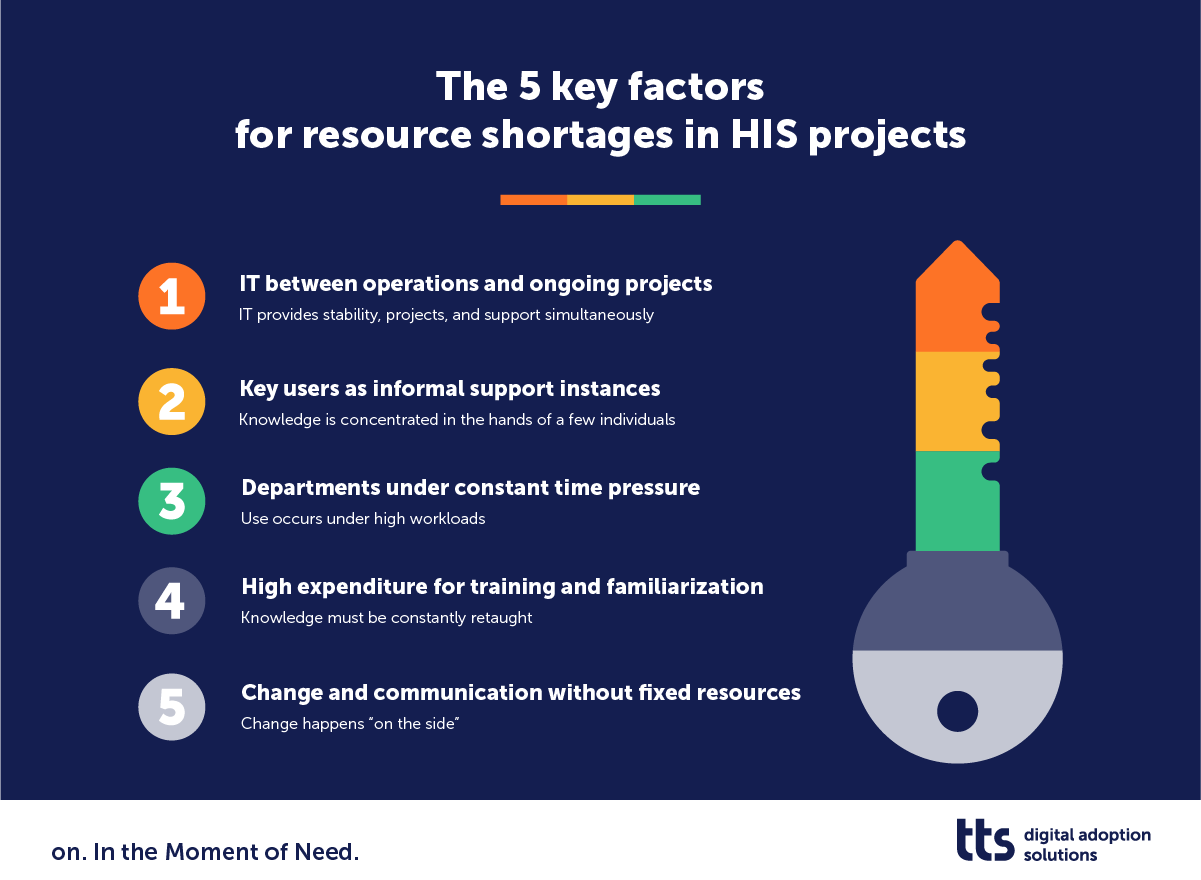

Resource shortages in HIS projects: a structural reality

What's more, HIS projects don't end with the go-live. They transition into operation—and often tie up more resources than planned. Support requirements increase, specialist departments need guidance, and key users become permanently involved. What started as a project becomes an ongoing task.

The bottleneck rarely occurs in a single place. It is spread across IT, specialist departments, training, change, and operations. It often remains unclear where resources are actually being used—and at which points targeted relief would be possible.

This article addresses precisely this issue. It highlights the five key areas where resource shortages have a particularly significant impact on HIS projects and provides a realistic assessment of where relief is possible—and where it is not. It is not intended as a promise of a solution but rather as guidance for decision-makers who are responsible for HIS projects under tight constraints.

IT and HIS teams between operations and projects

In many hospitals, IT teams have a dual responsibility. They ensure stable operations while also driving HIS projects forward—from implementations and migrations to releases and enhancements. Added to this are other digitization initiatives, such as those related to KHZG projects or interoperability projects.

This parallelism creates constant pressure on resources. Project tasks compete with day-to-day business, and unplanned support issues interrupt scheduled work. The situation becomes particularly acute after go-lives: usage-related queries increase, and IT becomes the point of contact for technical uncertainties, even though the systems are running smoothly from a technical standpoint.

The result is a familiar pattern. IT teams work reactively, strategic issues take a back seat, and project plans come under pressure. The actual bottleneck lies less in the technology than in the everyday use of the system.

Where relief is possible:

Reducing usage-related support requests can free up significant IT capacity. Digital support directly in the HIS helps to clarify recurring questions in the work process instead of passing them on to support. In addition, structured enablement and change approaches can help not only to manage support, but also to reduce it in the long term.

Where the limits lie:

This cannot solve a fundamental shortage of IT personnel. Digital enablement approaches can provide relief, but they cannot replace missing positions or unclear prioritizations.

Key users as bottlenecks in operations

Key users play a central role in HIS projects. They are familiar with the technical processes, support colleagues, test new functions, and mediate between IT and specialist departments. In practice, however, they usually take on this role in addition to their actual tasks.

After go-live, the situation often worsens. Queries come thick and fast, uncertainties in everyday work end up with the key users, and occasional support becomes a permanent burden. Knowledge is concentrated in the hands of a few individuals, who effectively become unofficial support centers.

This poses several risks for the hospital:

- Key users are overloaded

- Their actual specialist tasks suffer

- Absences or staff changes quickly create a knowledge gap.

The lack of resources is not evident here in terms of a shortage of staff, but rather in the dependence on individual persons.

Where relief is possible:

Knowledge can be extracted from the minds of key users and made directly available in the HIS. Context-related support in the work process ensures that recurring questions are answered where they arise. In addition, clear role models, realistic expectations, and structured enablement concepts help to stabilize and limit the role of key users.

Where the limits lie:

If key users are not formally exempt or their role is not recognized organizationally, the burden remains. Digital support can relieve the burden, but it does not replace clear regulations regarding responsibilities and time budgets.

Departments under constant time pressure

The success of a HIS project in everyday life is determined in the departments. Medical staff, nursing staff, functional areas, and administration work with the system on a daily basis—under considerable time and performance pressure. There is often little room for additional training, follow-up work, or in-depth examination of new processes.

In this situation, HIS changes often come “on top.” New functions, changed processes, or additional documentation requirements are added to an everyday routine that is already tightly scheduled. Uncertainties are not always addressed, but pragmatically circumvented. Workarounds are created, processes are shortened, or used differently than intended.

This is not without consequences. A lack of confidence in the system has a direct impact on the quality of data in the HIS. Information is recorded incompletely, inconsistently, or late. As a result, downstream processes such as billing, evaluations, or quality assurance come under pressure. Operations become more unstable, correction loops increase, and support costs rise.

At the same time, acceptance of further changes declines. Not out of rejection, but because every additional adjustment is perceived as a further risk in an already busy working day.

Where relief is possible:

Support directly in the work process can noticeably relieve the burden on specialist departments. Context-sensitive help in the HIS increases reliability of use precisely in those situations where data must be recorded correctly and completely. In addition, realistic change and training concepts help to make the connections between usage, data quality, and operations transparent.

Where the limits lie:

This cannot compensate for structural understaffing in clinical operations. Digital enablement approaches can reduce risks and ensure quality, but they cannot replace missing human resources.

Training, knowledge transfer, and familiarization under constant pressure

Training and qualification are indispensable in HIS projects. At the same time, they are among the areas where resources become scarce particularly quickly. Face-to-face training courses are time-consuming, difficult to schedule, and can only be scaled to a limited extent in shift operations and high utilization. Digital learning formats help, but do not completely solve the underlying problem.

Added to this is the high pace of change. Content quickly becomes outdated, new functions require updates, and in the event of staff turnover or external personnel, training has to start all over again. The effort is spread across many training sessions, repeated explanations, and individual queries.

The consequences are evident in everyday life. Knowledge is fundamentally available, but not always where it is needed. Under time pressure, employees resort to assumptions or habits. This not only increases the need for support, but also affects the quality of data entry, for example when functions are used incompletely or process steps are skipped. Corrections are made downstream and tie up additional resources.

Where relief is possible

A stronger integration of learning and working can provide noticeable relief here. Support directly in the HIS reduces the need for repeated training and provides knowledge exactly when it is needed. In addition, didactically well-designed qualification concepts help to tailor learning content to critical usage situations instead of conveying it in a broad and abstract manner.

Where the limits lie

Formal mandatory training, certifications, or regulatory requirements cannot be replaced by this approach. The initial qualification effort for complex systems also remains. However, digital enablement approaches can help to better distribute this effort and reduce it in the long term.

Change and communication “on the side”

Change is omnipresent in HIS projects. New processes, adapted workflows, additional documentation requirements, or changed roles are part of everyday life. Nevertheless, change is often not planned as a separate task, but rather “taken on” by project managers, IT, or key users in addition to their day-to-day business.

Communication then takes place sporadically, often with a technical focus and under time pressure. Departments learn about changes late or in a form that offers little guidance. What is changing in the system is known—why something is changing and what this means for their own everyday work often remains unclear.

The effects quickly become apparent. Uncertainty increases, rumors arise, and acceptance declines. Changes are implemented hesitantly or only partially. This not only leads to delays in the project, but also ties up additional resources in the company: queries increase, coordination becomes more frequent, and IT and specialist departments have to take corrective action.

Where relief is possible:

A structured approach to change creates clarity here. Early involvement of relevant stakeholders, clear communication based on actual usage situations, and a clear separation between information, training, and support noticeably relieve the burden on project teams. In addition, support directly in the work process can help to anchor changes where they need to be implemented.

Where the limits lie:

Change cannot be delegated or automated. A lack of prioritization, unclear decisions, or insufficient support from management cannot be compensated for even by good concepts. Enablement can provide support—but responsibility for change remains with leadership.

Conclusion: Recognizing a lack of resources means providing targeted relief

A lack of resources in HIS projects is rarely the result of individual wrong decisions. It arises where high complexity, constant pressure to change, and limited personnel capacities converge. In many hospitals, it is therefore not a temporary problem, but a structural condition.

The crucial point for CIOs and IT managers is not whether resources are scarce, but where they are tied up. This article has highlighted five key bottlenecks: IT and HIS teams caught between operations and projects, overworked key users, departments under time pressure, permanently required training structures, and change and communication that run alongside everything else.

Not all of these bottlenecks can be resolved. Staff shortages, regulatory requirements, and structural conditions remain. At the same time, a look at these areas shows that a significant portion of resource consumption is caused by uncertainty, repetition, and follow-up adjustments.

This is precisely where effective levers can be found. Where usage becomes more secure, knowledge is available in the work process, and changes are accompanied in a transparent manner, the need for ad hoc support, corrections, and escalations decreases. Relief does not come from additional projects, but from targeted measures that stabilize operations.

For CIOs, this means that resource shortages are not purely a quantitative issue. They are also a question of enablement, change, and the way in which HIS projects are integrated into everyday clinical practice. Taking this perspective creates room for control—even under tight conditions.